Why 'Critical Race Theory' Is Nothing to Fear

"Learning the truth about my own hometown's history opened my eyes to the larger educational challenge in America."

By Dan Goldfine

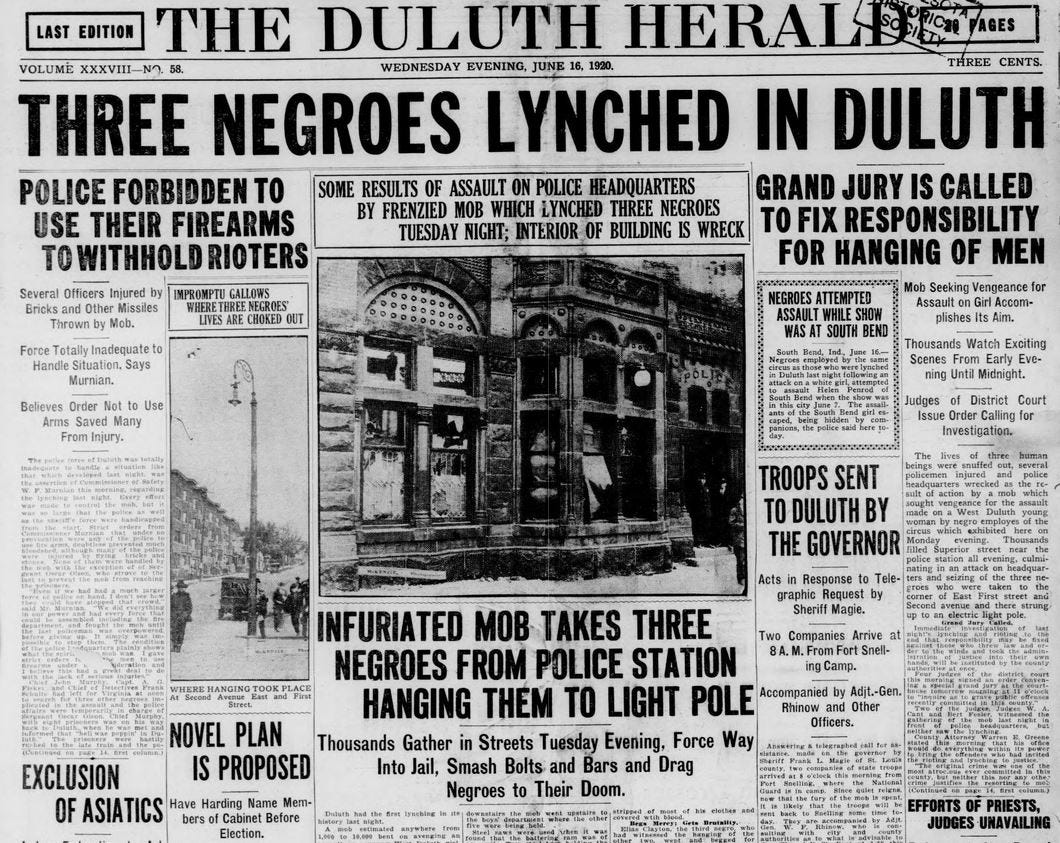

In the 1990s — after controversies about “critical thinking” settled down — someone asked me to help fund a memorial to the three men who were lynched in Duluth, Minnesota, in the summer of 1920. I responded that there had never been a lynching in Duluth. I was wrong.

There are few cities in the United States farther north than Duluth. The Duluth schools of the 1960s and 1970s taught me that lynching was a “Southern” problem. But research reveals that lynching was — and is — an American problem.

Why did Duluth schools not teach me about the 1920 lynchings in Duluth? Why did the approved curriculum treat lynching as an exclusively “Southern” problem?

The Duluth Lynching

In June 1920, an out-of-town circus put up tents and performed in Duluth. A 19-year-old woman watched the dismantling of the tents. Afterwards, she claimed to her dad that five or six Black circus workers raped and robbed her.

The next day, her dad called the police to report the alleged crimes. The alleged victim was examined by a doctor working for law enforcement, who found no signs or indications of sexual assault.

Later that day, the Duluth Police Chief lined up 150 of the “usual suspects.” It is unclear whether the alleged victim identified anyone. Shortly after the lineup, the police arrested six Black circus workers, charging them with rape and robbery. They were placed in the city jail.

That same day, the evening newspapers reported the alleged crimes, as well as the arrest. A mob of men, estimated at 10,000, formed outside of the city jail. At the direction of police leadership, officers cooperated with the mob.

The mob seized three of the men, Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson and Isaac McGhie. It then held a fake trial, convicting the three men.

After the “verdict,” the mob took the three men to the center of Duluth, where they beat and hung them from a light pole — lynching and murdering them.

Two days later, the Duluth police arrested five more Black circus workers. Charges against five of the seven in custody were dismissed. Two of the men, Max Mason and William Miller, were tried for rape. Miller was acquitted, but Mason was convicted and sentenced to 30 years.

After four years, Mason was released. In 2020, the state of Minnesota pardoned him.

Schoolin’ in Duluth Then

The names of the textbooks used in Duluth schools in the 1960s and 1970s escape me. Their discussions of lynching do not.

The Duluth textbooks treated lynching as a Southern problem limited to the periods of slavery and Reconstruction. There were pictures of Black men lynched, white men belonging to the KKK, and a lynching tree. Not a word about lynchings in the North. Classmates, cousins and siblings of mine confirm there was never a mention by any teacher about the Duluth Lynchings during the 1960s and 1970s.

In one textbook, a few pages after a photograph of a lynching tree, a discussion of The Great Migration takes place. It is described in a strictly positive light.

Because of Critical Race Theory, beginning in the early 2000s, curriculums and textbooks in Duluth schools changed. They took a more holistic approach to lynching and racism in America — and in Duluth. I am told that Duluth teachers now openly discuss the Duluth Lynchings, the victims, and the underlying racism. The teachers unveil for children that evil can be found anywhere and must be addressed. Armed with the truth — anyone can be an advocate for justice.

Critical Race Theory or “CRT”

CRT is an offshoot of critical thinking or theory and has been around since the 1960s. It asks how public actions, such as the police cooperating with a mob or school officials selecting textbooks, are infected by racism and implicit bias. In a legal context, CRT asks whether certain laws — even color blind laws — perpetuate implicit biases, inequality and racism.

Albeit broader, critical thinking challenges and analyzes existing power structures. Some of these structures, in government, at universities and at law schools, grappled with critical thinking — trying to shut it down. Slogans abounded, with many calling critical thinkers “Marxists.” But by the mid-1990s, critical thinking had subsumed a role in academia and political discourse.

Some of the slogans used to attack critical thinking in the 1980s have recently rebounded in new attacks on CRT. Seeking bans on CRT, lawmakers have called it “Marxist,” “indoctrination,” “racist,” and “anti-American.”

But just the opposite is true: The use of inaccurate or misleading textbooks is harmful. And the promotion of laws that are textually color-blind can be just as harmful — as it was in the Duluth of the 1920s and during the time when I grew up. It is counterproductive to the mission of education. Barring criticisms of textbooks and curricula in schools is similarly flawed.

What I know with certainty is that my teachers misled me. They wrongly educated me that racism was not a Duluth problem. They concealed racism in the North by saying lynching was a “Southern problem” and by ignoring our city’s own history of lynching and racism.

And what I also know with certainty is that public school teachers are being forced in Florida and other places not to teach their students the full and accurate history about the evils of slavery and other intentional mistreatments of Black Americans.

If this is caused by the mere ignorance of policymakers and their constituents — which is incredibly difficult to buy as an excuse in the year 2023 — my hope is that this story about my own education will open up some eyes and minds.

If, on the other hand, these are strategic decisions to hide history driven by real bigotry or by a fear of acknowledging America’s true and full track record, more soul searching will be required to turn the tide. And elections.

Facing our history — by telling the truth — is an exhibition of strength, not weakness. No person is perfect. Nor any country. Nor ideology.

As one of my JEWDICIOUS colleagues, Rabbi Mari Chernow, is fond of saying:

“Good judgments come from experience. Experience comes from bad judgments.”

Exactly. And owning up to our own shortcomings is not only the right thing to do — it’s an act that is usually worth its weight in gold in the long run.

Dan Goldfine is an Attorney at the international law firm Dickinson Wright and a former Federal Prosecutor at the U.S. Department of Justice, Antitrust Division.

If you like what you see at JEWDICIOUS, please share our stuff with family and friends — annual subscriptions to all content from our “Original 18” are FREE till the end of 2023!

From unpacking history and politics to navigating the nuances of family and personal relationships to finding the human angle on sports and entertainment — plus our unsparing take on what’s happening in the Jewish world — the canvas at JEWDICIOUS is limitless! JOIN US!!

Everyone with a conscience and a just seeking mind should read this article and pass it on to those who are still clinging to attitudes and prejudices still prevalent today. It is deeply disturbing to realise what can and does happen when extreme views go unchallenged.

Exceptional article. Thanks