Maslow and Me: The Right Teacher at the Right Time

"Suddenly, I had an answer to my frustrating and painful attempts to find a direction in life. I felt as though I had discovered the Holy Grail!"

By Michael S. Lewis, M.D.

In the summer of 1960, I arrived as a frightened, insecure, and directionless freshman at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. Most of the students were from the metropolitan New York or New England area. By comparison, my hometown of Houston, Texas, in the 1950s was like the Wild West. I felt like a hick surrounded by sophisticated Yankees. I was overwhelmed by the quantity and difficulty of the classroom assignments, and in those first few months, I felt especially alone and troubled.

Of all my classes, the one that excited me the most was Abraham Maslow’s class on self-actualization. In the 1950s and early ’60s, he revolutionized the field of psychology. Instead of focusing his work on people who were struggling, and often failing, to cope with life’s challenges, Maslow chose instead to study people who were leading successful, healthy, relatively satisfying lives. He tried to discover how they got that way. He called these people “self-actualized.”

Suddenly, I had an answer to my frustrating and painful attempts to find a direction in life: Discover what self-actualized people are like, and try, if possible, to emulate their qualities. What an electrifying idea! I felt as though I had found the Holy Grail.

Many of Maslow’s students were too intimidated to take advantage of his office hours, but I wasn’t going to miss the opportunity. I took an ancient Chinese proverb literally: “Teachers open doors, but you must enter by yourself.”

Abraham Maslow became a mentor. I developed a close personal relationship with him. Like all the best teachers, he continually expected more and insisted on greater effort. It was in his cramped office, piled with books and papers on every surface, that one of my rare, life-changing epiphanies occurred. It happened during my junior year, on Wednesday, March 13.

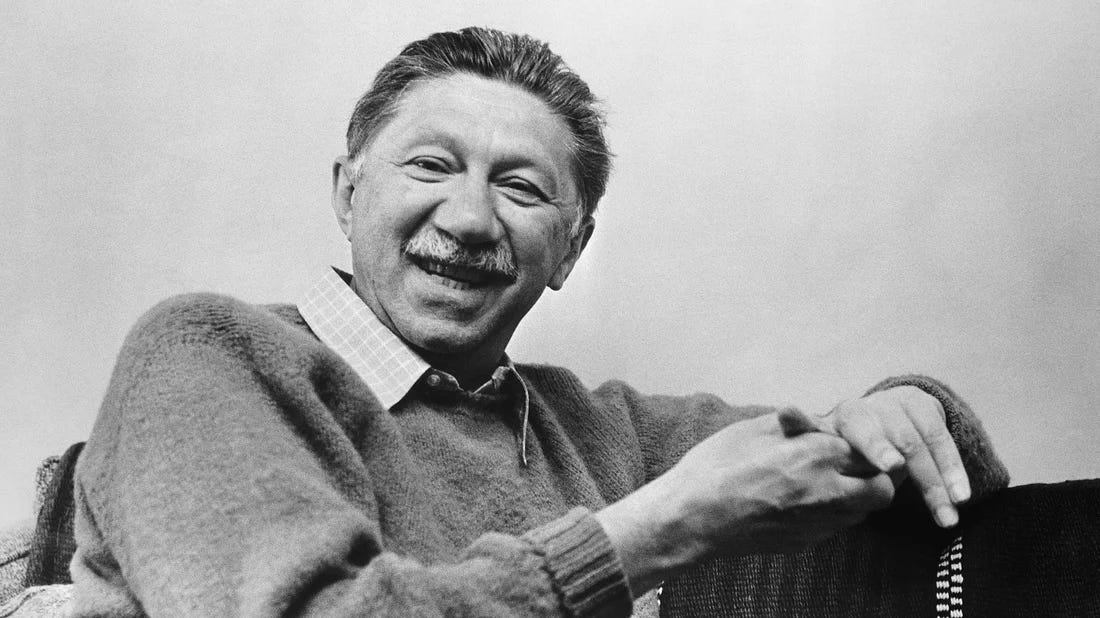

Maslow had a round face, a large nose, and a bushy mustache. He always wore a tweed jacket, white shirt, and tie. He had a permanent twinkle in his eye, but for a moment he looked at me solemnly and said, “Someone is going to make significant contributions in the field. Why shouldn’t it be you?” Hearing those words from the master, I was immediately struck in the chest by a thunderbolt of energy that surged through my body. The future of psychology could be in my hands!

At the time, there was a hierarchy in the field of psychology, with psychiatrists at the top of the food chain. Abraham Maslow, being practical as well as idealistic, told me, “The best way to make an impact in our academic domain is to become a psychiatrist. You need to apply to medical school.”

Most of my premedical classmates seemed to know almost from birth that they were meant to be physicians. I decided only after my junior year, primarily because the “big kahuna” suggested the idea. (My journey during medical school from impacting the world of psychiatry to becoming an orthopedic surgeon is a story for another time).

It has been more than 60 years since that day in Abraham Maslow’s office, but I can still feel the deep-seated jolt of confidence those words conveyed. Duke basketball coach Mike Krzyzewski said, “‘I believe in you’ is maybe more important than ‘I love you.’” It is astonishing to me how at a particularly vulnerable moment, someone we respect can change our lives by boosting our self-assurance and courage. I try to remember that when dealing with children, grandchildren, students, and patients.

I feel so fortunate that Maslow’s guidance was available when it was so desperately needed, and I was deeply touched by his kindness to me personally. Having a direction, I journeyed out of despondency. It wasn’t one “Aha!” moment, but rather a slow-moving avalanche, steadily gathering strength from interactions with Maslow and my other professors and their ideas.

Maslow continues to capture my imagination and to immeasurably enrich and expand my world. I have published Seeing More Colors: A Guide to a Richer Life, a book entirely devoted to him. On some level I’m still trying to fulfill the promise he saw in me.

It’s difficult to emphasize how important it is to seek out teachers and mentors that one admires. In my opinion, having mentors is greatly underappreciated in our society. They can see potential in you that you do not — and help you to achieve things you didn't think possible.

“Each of us has cause to think with deep gratitude of those who have lighted the flame within us.”

— Albert Schweitzer, physician, theologian, and Nobel Peace Prize recipient

MICHAEL S. LEWIS, M.D. is a former Orthopedic Consultant to the Chicago White Sox and the Chicago Bulls, and the author of seven books.

From decoding politics to the cutting edge of wellness to the human angle on sports to parenting and personal relationships — plus our unsparing take on what’s happening in the Jewish world — the canvas at JEWDICIOUS is limitless. Our 18 scribes share one overarching goal: To present you with new ideas and slices of life that will hit your head or touch your heart!