I Learned About Grief from My Dad

"I don’t think we give enough acclaim to quiet heroes, to those who take care of things which are small in scale but unbearable in emotion. My hero is my father, a mentor in both life and loss."

By Debbie Weiss

Widowhood seems to run in my family.

My father, Morton, lost my mother in 1973. She left him with a suburban ranch house, a spoiled white cat, and a shy ten-year old daughter (me). He was a physicist, and like most men of the time, he wasn’t very involved in child-rearing. Being a single dad was uncharted territory as he moved from doing weekend planetarium visits to providing 24-hour care, and from having a loving partner to being alone.

He transformed himself.

He learned how to make burgers and meatloaf, later salads and fish, and always lots of broccoli. He hosted my birthday parties and even got my friends to eat zucchini. When I was in high school, we’d watch cooking shows on PBS and he’d tackle the main course while I baked the desserts.

Behind the scenes, he took classes in meditation and Buddhism to deal with his new life. He listened to hours of my adolescent angst, a huge accomplishment since I used to joke that “patient physicist” was an oxymoron.

We read books together; Hermann Hesse was a particularly hard sell. And being my father, he was never concerned that I was a high school pariah who did Book Club with Dad and spent Saturday nights throwing dinner parties for physicists.

If he ever felt sorry for himself, or thought I was a burden to him, he never let on.

He just did what needed to be done. He was a super competent, if over-involved, parent. When I was 15 he let me go to a rock concert on a double date, but not without many, many hours of advice beforehand. He was both a Jewish father and a Jewish mother.

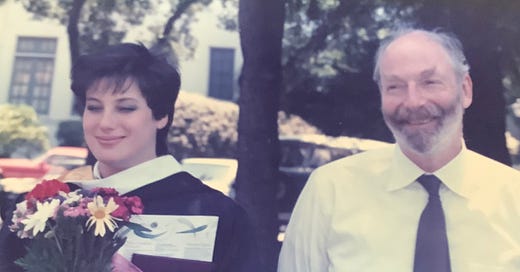

Together we decided I would attend Mills College, a small women-only liberal arts college, and we picked out my classes together so “we” didn’t take anything too easy. He helped me with my calculus homework although he was a bit overqualified.

Despite losing my mother, I had a wonderful childhood filled with books, homemade chicken soup, and too much opera. Other than becoming a lawyer, I turned out okay. And when I burned out at a relatively young age, he never complained about having paid for three years of law school.

But nothing prepared me for my husband George’s death from cancer at age 53 in 2013. My first thought: this can’t be happening again. I had such a tiny family yet once again I was losing the person I loved the most.

George and I were both anti-social introverts. We were each other’s best, but unfortunately, almost only, friends. At first, I thought I’d die from the widowhood effect, where the surviving spouse dies relatively soon after losing their partner, especially if they were their caregiver, as I was. I felt prematurely old despite being only 49.

But when I felt hopeless after my loss, my dad was my role model. He’d found a way to go on, and even flourish, after my mom died. I would too. As in all things, he had lots of advice. Do venture out and make friends, don’t make any drastic changes, and yes, life will get better over time. He encouraged me to travel and to take a few, though very prudent, risks.

Part of grief is waiting, trying to make the days bearable until being able to see light, a small ray to begin with, then a bigger hole in the darkness, and later, possibly even years, seeing in color. Over time ― though far more than I expected ― life got better. The emptiness filled with synagogue groups, yoga adventures, and later a graduate degree in writing. But mainly life got better because I learned to love people.

At the right time, Dad encouraged me to start dating again. Although he warned me that the pool of good available middle-aged men might be pretty small. In the nineteen-seventies, when he’d been dating, many women told him he was the only man they'd met who acted like an adult. He used to joke that he was "The Bay Area adult male."

After a few years of dating, he found my stepmother, a pediatrician who was one of seven women in her medical school class. When he first met her, he thought she was too young for him (she’s twelve years younger), but she firmly told him she wasn’t. Most men ran away when she told them that she was a doctor, but Morton said, “tell me more.”

After some time online on J-Date, I too started to think my Dad had been the only Bay Area adult male since the seventies. But after five years, I found love again. With someone who was totally different from me, relaxed, where I’m anxious, spiritual, where I’m cynical, an athlete to my nerd. But we’re aligned in our values, which we both learned from our respective fathers.

Without my dad, I never could have borne my loss. He was my model for how to survive a terrible loss and to emerge a better person. Despite losing my mom, he found and shared so much joy, from getting cake at a museum with a sad daughter to grilling salmon for visiting scientists.

Our secular society seems to rush through grieving. People want to hear we’re better and “over it,” and in the case of losing a spouse, that we’ve “moved on.” When I lost my George, so many people said that I was still young, I could find another person, as if I could just order a new partner on Amazon Prime. \

We don’t teach people how to cope with loss. Processing grief takes time and reflection. In my case, it meant realizing I deserved a good life even though George’s had been cut short. And it meant getting off the sofa when I didn’t want to and changing my life to match a new reality. But as with most things, I learned from my father.

These days, Morton is 94 and still super sharp, still listening to my problems and offering advice. He takes care of my stepmother who has memory loss, but she’s still radiant and happy to be with him. Once again, he never complains or seems dejected. He just does what needs to be done, providing a life for the person he loves.

I don’t think we give enough acclaim to quiet heroes, to those who take care of things which are small in scale but unbearable in emotion. My hero is my father, a mentor in both life and loss.

DEBBIE WEISS is a former lawyer, essayist, and the author of Available As Is: A Midlife Widow's Search for Love.

From unpacking history and politics to navigating the nuances of family and personal relationships to finding the human angle on sports and entertainment — plus our unsparing take on what’s happening in the Jewish world — the canvas at JEWDICIOUS is limitless! JOIN US!!