By Andrew Rashkow

Animals survive on their instincts. Even a casual observer can note the amazing feats that are seamlessly woven into the routine existence of fauna. Whether fleeing to higher ground before flood waters hit, finding prey in a seemingly barren landscape, or suddenly blending into the background in a camouflaged retreat, each species appears naturally hardwired to act in ways that provide their best chance for survival.

But while we may appreciate and admire these innate traits, we shouldn’t fall prey to the notion that this intuitive mode of action marks the pinnacle of existence.

Instinctive behavior is animalistic.

Of course, that doesn’t make resulting actions necessarily wrong, but it does mean that we forfeit an essential part of our humanity whenever we take actions unmediated by our intellect. We have been given a unique, God given gift that we should not squander: the ability to consider if any given impulse or instinct should be encouraged or constrained. I would argue that a more contemplative approach of carefully choosing our actions is, in fact, somewhat counterintuitively aligned with the current zeitgeist which lauds the spontaneous and the impulsive — while still leaving ample room for improvement.

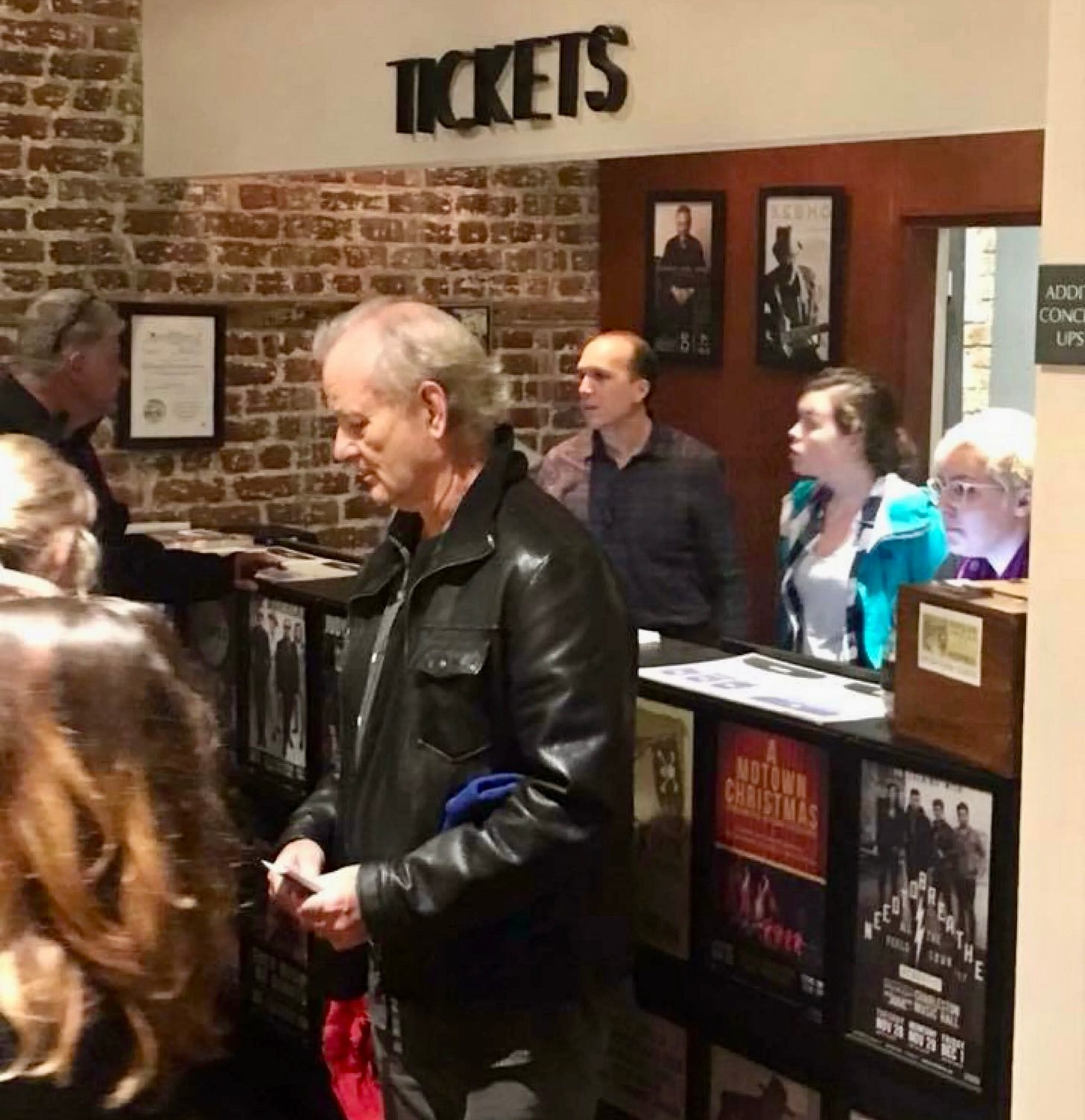

The world’s leading shaman of “living in the moment,” Bill Murray, may be as likable and approachable as he appears, but his improvisational approach to life may still forsake too much of heaven and earth, to paraphrase Hamlet. What if an allegiance to the ephemeral precludes the possibility of connecting to the eternal? It would seem that the same aversion to rote behavior should apply equally to that which is rash and careless, since mindlessly going through the motions is precariously close to simply running on instinct and winging it.

This pernicious tendency towards autopilot becomes even more perilous in the cerebral sphere. When left unchecked, opinions and feelings often form before any real examination of an issue or its underlying causes occurs. The contemporary flow of “information” – to label it kindly – has long since bypassed the traditional culling process of research, writing, editing, and publishing. We are all too familiar with the phenomenon whereby people put more time and energy into consuming and responding to material than was ever put into the original thought that spurred the reaction. The point I’m driving at here is that any strong viewpoint which has not been subjected to critical thinking is really nothing more than an empty notion masquerading as a deeply held conviction.

Real wisdom is the result of seeing as many sides as possible of an issue and from that informed perspective choosing the one which is most compelling. The process of endeavoring to understand why another intelligent and well-intentioned person holds a certain view, even if we ultimately disagree with it, not only fortifies our own thinking and position, but humanizes the other side as well. This creates the possibility for dialogue, and in some undeterminable measure, it increases the prospects for peace and happiness. Conversely, the out-of-hand dismissal of every viewpoint other than our own without consideration of their merits results in fragile, jingoistic beliefs that leave the world a little harder and a little colder.

The Jewish tradition is one that questions from its origin. The very moment before Moses first encountered God at the burning bush, the question of “how can this fire burn and not consume?” hung in the air. There has been an ongoing dialogue ever since. Our sages describe two different ambulatory trajectories of a snake — one which zigzags from side to side, and the other that slithers in a straight line. Both approaches are necessary to pursue the truth, chasing some promising leads down dead-end alleys which force us to turn about, while at other times holding steady to the course when we’re fortunate enough to have gained a target lock on something we recognize as true.

A good place to begin a mindful pursuit of truth is with silence. In an increasingly distracting, disjointed and tumultuous world, our ability to listen – and really hear – largely depends on our ability to lower the noise levels both inside and outside of our collective heads. And then from an independent, quiet place, we may choose — carefully, slowly, and deliberately — to let in one thing at a time for careful consideration. Shema Yisrael.

Andrew Rashkow is the CEO of Imbibe, Co-founder of Heaven’s Door Spirits, and a Jerusalem-based Teacher and Adviser.

Free subscriptions to JEWDICIOUS are available until the end of 2023!

From decoding politics to the cutting edge of wellness to the human angle on sports to parenting and personal relationships — plus our unsparing take on what’s happening in the Jewish world — the canvas at JEWDICIOUS is limitless. Our 18 scribes share one overarching goal: To present you with new ideas and slices of life that will hit your head or touch your heart!

This is a thoughtful presentation of the deep consideration of first principles that lies at the heart of connection to our tradition. Really enjoyable piece!

Terrific piece!