All That We Can't Leave Behind

"It’s as if there is a rope that connects us to the past, and no matter how far we get from the history of trauma, it’s hard to let it go."

By Leah Eichler

Author and Polish-American lawyer Samuel Pisar once famously said: “We may not live in the past, but the past lives in us.”

It’s a sentiment that’s resonated with me for most of my life – but has taken on added significance since the October 7 massacre. To say that the attack struck a nerve in Jews around the world would be a new form of understatement. Our shared history creates trauma that lives in our bones. This isn’t just a literary conceit; it’s been scientifically proven that traumatic events leave a chemical mark on people’s DNA. What interests me most is not the genetic markers of pain, but how that pain shows up in art and literature. The familiarity is cathartic, even when it’s haunting.

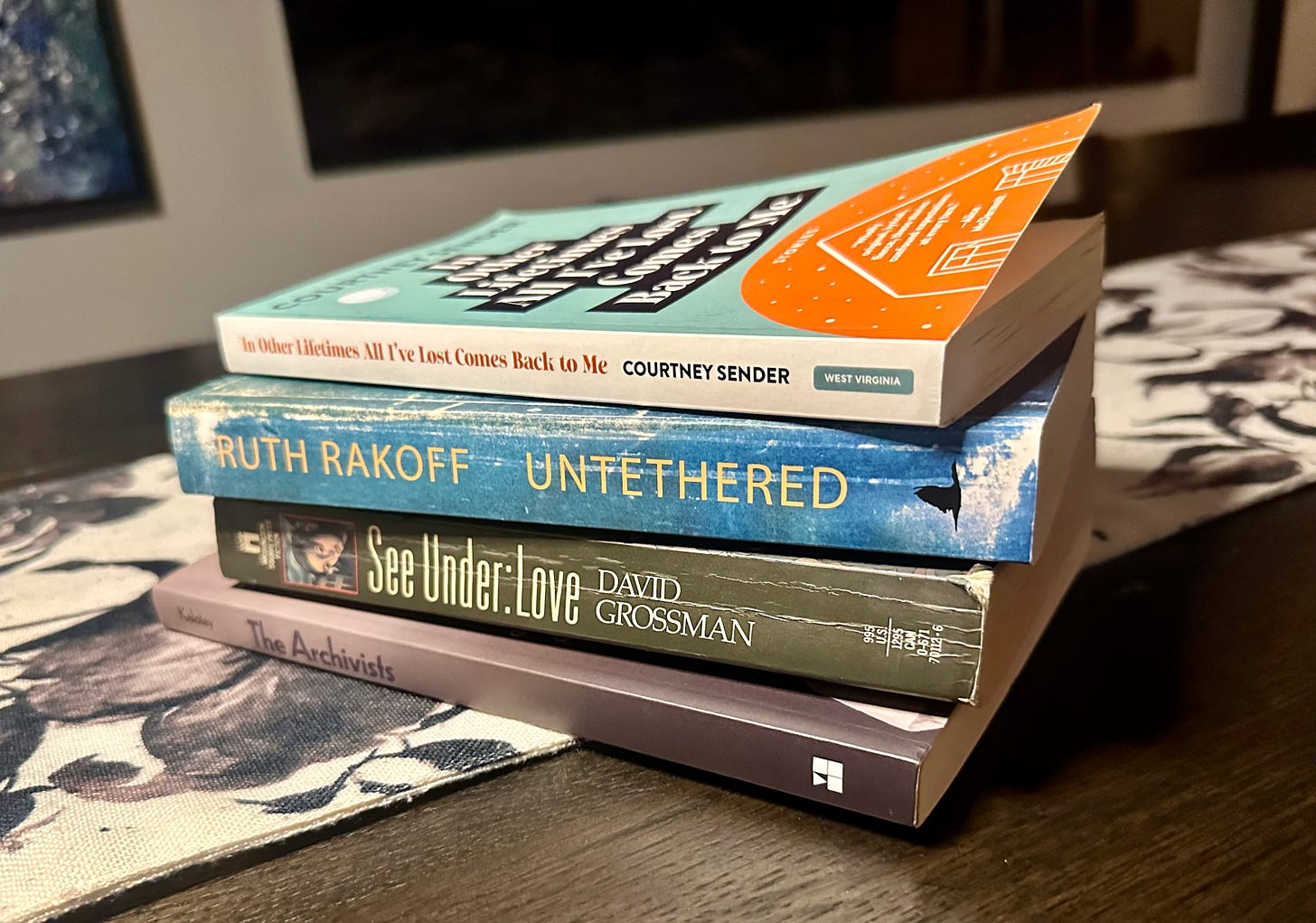

Several works of fiction published in the last year tackle this theme of the impact of intergenerational trauma that the Holocaust cast upon its descendants. I’d like to share a few with you.

The first, In Other Lifetimes, All I’ve Lost Comes Back to Me, is a collection of short stories by Courtney Sender. The book’s themes tackle love and loss, but the lingering impact of the Holocaust comes through. This is especially the case in her story, Black Harness, where two young lovers, Olivia and Gus, find themselves at a hostel in Berlin and decide to visit the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

“(T)he camp had held political prisoners, not Jews. Gus’s ancestors hadn’t guarded there. Olivia’s hadn’t died there,” Sender writes. The young lovers believe this to be a neutral ground, allowing them to reconcile their shared history. But they soon discover that their love cannot weather the storm. Right when they disembark from the tour bus, their guide begins a roll call and the buried memory in Olivia’s bones comes flooding back in emotional and physical ways, leaving the reader to believe that the lovers will never recover from the experience.

In I Am Going to Lose Everything I Have Ever Loved, the protagonist laments being 37 and not having had a baby yet to replace the dead her grandmother lost. Sender distilled this notion even more directly in an interview with Electric Lit:

“I think that some of my characters feel a very strong burden and responsibility from being in this line of the living.”

It’s as if there is a rope that connects us to the past, and no matter how far we get from the history of trauma, it’s hard to let it go.

Ruth Rakoff’s novel refers to this rope specifically in her recent novel, Untethered, which takes place in my hometown of Toronto. The book follows twins Rose and Petal as they navigate life being raised by their Holocaust survivor grandparents. One sister, Rose, becomes frum (embraces Orthodoxy), while Petal veers in a completely opposite direction.

While both sisters suffer from different mental health issues, they both independently find ways to mitigate their grief, either through self-harm, excessive education and therapy, or faith. But nothing quite heals the wound that binds these sisters to each other and to their shared history of trauma.

Meanwhile, in Daphne’s Kalotay's short story collection, The Archivists, the impact of trauma on one’s DNA is tackled head-on. The book’s eponymous story, “The Archivists,” is told by different generations of the same family, but their stories slowly collide. It begins with a grandmother, a Holocaust survivor who is expecting blue hydrangeas for her birthday – the exact color of a boy’s eyes she knew long ago. In a different city, her daughter, an aging ballerina, tries to resuscitate a famous dance that was never meant to be captured on film. Then the story pans out to include the granddaughter, who lives in a different time zone where she works in a laboratory examining the genetic impact of trauma – and the marker it leaves on not only the DNA of one’s children, but grandchildren.

In this story, the memories of what could have been are passed on from mother to daughter to granddaughter, who each in their own way want to capture some evidence of a world that’s been erased. Any descendent of survivors will immediately relate.

These are all recent books that have been published within the last year; it is by no means an exhaustive list. One of my favorite novels on intergenerational trauma remains David Grossman’s See Under Love. That book, and all of Grossman’s others, offer unique insights into not only intergenerational trauma, but Israeli life.

As I share these book recommendations, I would be remiss if I did not report that Jewish authors have lately been facing a new wave of antisemitism in the form of negative reviews on Good Reads or magazines and publishers refusing to look at submissions with Jewish themes or by Jewish authors. Most recently, Guernica Magazine retracted a personal essay written by an Israeli literary translator about navigating her cross-border friendships since October 7, after a number of their volunteer staff members resigned in protest.

One way to combat this dangerous trend and live up to our identity as People of the Good Book is go out and buy a few more of them!

Leah Eichler is an author, essayist and publisher of Esoterica Magazine. She's currently working on a blended memoir about contemporary Jewish identity and the legacy of the Holocaust.

From unpacking history and politics to navigating the nuances of family and personal relationships to finding the human angle on sports and entertainment — plus our unsparing take on what’s happening in the Jewish world — the canvas at JEWDICIOUS is limitless! JOIN US!!